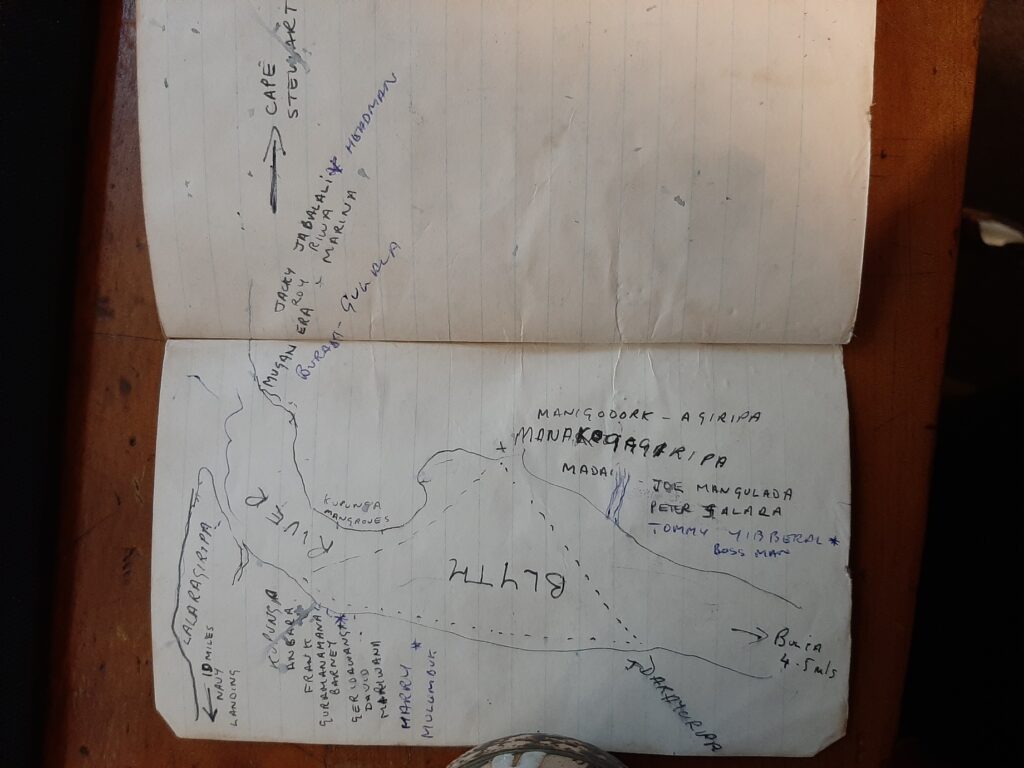

As the 1974 Dry Season extended my capacity to move, I went out to Kupunga for a week. My agenda included trying to further several Aged Pension verifications, enrolling eligible adults onto the electoral rolls (Whitlam had dissolved both houses of parliament and called an election for mid-May) and seeking direction from the community leaders of their development priorities. My diary of that week makes for fascinating reading and is worth selective reproduction. It follows:

I have chartered Tommy Yibberal’s boat and spent the early morning loading shop stores. Tides were against us and it meant using a small dingy to ferry supplies out to where Tom’s boat was moored. Seven trips, each with a tricky balancing act of passing stuff up from the wobbly tinny. Tom, Dan Gillespie and I got underway at 10am, moving downstream, out of the river, passing Entrance Island on our right-hand side, before heading east along the coast.

We entered the Blyth River six hours later and made the short trip upstream. Barney Geridawanga, some of his smaller children and Jackie Gumboa met us as we drew up adjacent to the community. Barney told us that most of the mob were out hunting.

It is quite a steep embankment, and the two old men were unable to help us transfer the supplies up onto the dry embankment. We laboured and were joined in the unloading by Tony Monalia and Tommy Steele Gondara.

By last light, most of the community had made it back, laden with yams, geese, a wallaby, and a few fish. Under torchlight, the resident school teacher, David Mirawanga (a former Teacher-Aide from Maningrida) distributed the Social Security Pension and Child Endowment cheques. I proceeded to get people to endorse their cheques with their signature, or mark – generally a cross. Some preferred to use an inked thumb-print, and in the spirit of an audit, I countersigned that mark, before exchanging the cheques for cash!

Over the next couple of hours people came and went. There was a boatload of ten people arrived from across the river to shop. Priority items were secured first – flour, sugar, tea leaf, shotgun shells, then followed by items to quieten excited children, with the purchase of chips and soft drinks! There were still some shotgun shells, cigarettes, chewing tobacco, a few tins of meat and powdered milk left at end of the shop.

Barney, Frank Guramananna, Tommy Steele, Tom Yibberal, David Mirawanga, Jackie Gumboa, and a few others sat with Dan Gillespie and I around a smokey fire. We talked about:

the upcoming election and the opportunity to get on the rolls; the scheduled visit of long-time Adviser, John Hunter, to introduce Andy Hazel, the new Community Adviser;

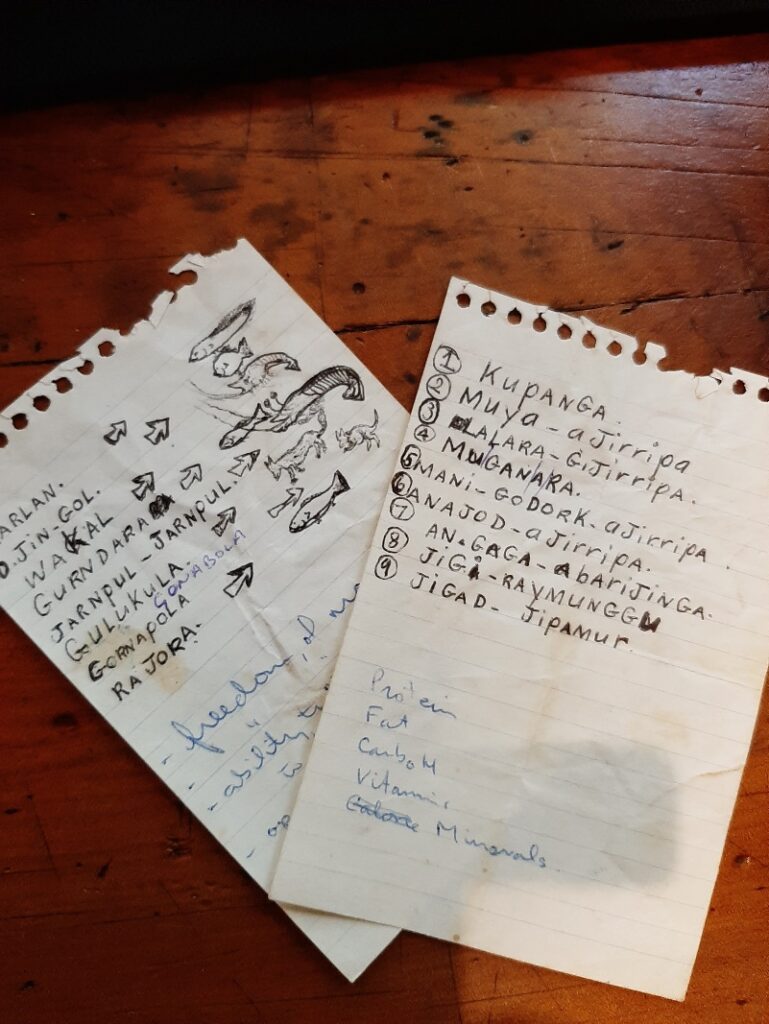

the question of accessing a beer ration at the outstation; the need for extra building materials to finish the bush timber school-house. There was mention of some research being proposed by the Health mob, looking into the nutritional value of bush tucker! [In defense of the appalling nutritional value of the just completed ‘shop’, this might be very worthwhile. However, it should be further noted that the diet of the community was generally inordinately met from hunting!]

Dan, Tommy, and I were allocated space to unroll our swags on the sandy floor of the school lean-to. A stiff, cool wind promised a mosquito/sandfly-free night.

There was a little residual shopping done next morning from those with cash. Dan and Tommy departed at 9.30, heading for Maningrida. They advised a return, with John Hunter and Andy Hazel in four days’ time.

As the boat disappeared around the Lalal-a-girripa headland, an informal discussion around “botin bizness” started. I had brought out paperwork relating to the Electoral Roll and I helped complete Postal Ballot applications for Frank, Barnie, Jackie, Nancy Bandiama, Margaret Mangawaij, Tommy S, Paddy Gunabaitja and David. I also enrolled several young men and women.

Others drifted in on the discussions, others drifted away as the demands of the morning dictated. Talk turned to the future of Kupunga. I asked what would happen if the Government withdrew its support for the fortnightly mobile shop visits? I was forcefully reminded that John Hunter had previously assured the mob of continuing help! I reiterated my belief that that was not under threat –I had stupidly and unnecessarily cast doubt on this commitment and spent time reassuring the community!

We talked about buying another boat, noting the dead 17’ Seamaster boat, and motor beached not too far away! Could it be a collective purchase between Kupunga and three other nearby Burada/Anbarra outstations? No one was keen on that – its location, maintenance, and operational responsibilities!

Someone suggested an all-weather road back through Balpinada Swamp to connect to the Cadell road. It was agreed that for most of the year the 15 miles of swamp was impassable. Maybe along the coast to Ngakala-mandjara? Again, the three creeks would prove impossible.

Talk drifted, as did the residents. Postal Ballot applications had been discussed with shoppers from across the river the previous evening so Tommy Gandara, Paddy Gunabardga and I borrowed the dug-out canoe and with paddles and a little assistance from a small sail, went to Manakadok-a-jirripa outstation.

This canoe – Lippa-lippa – was the one I saw Barney Geridawanga making at the Cadel Gardens two years earlier. It has subsequently been fitted with a small, outrigged pontoon but still wallowed, and made heavy going against the tide. I took a photo of Barney, with his granddaughter sitting in the canoe in 1971.

Barney and granddaughter, 1971. Lippa lippa emerging from the paperbark tree.

The Blyth River still has a very healthy population of salt water crocs and in our crossing, we saw three or four lying at the high-water mark. Our approach had them quickly up and slithering down into the river. So many crocs but the community seems to live in apparent harmony with them! The kids splash and swim in the shallows below the community, people fish at the water’s edge, and I know people occasionally swim across the river!

I wondered whether the crocodile shooting/skin trade had ever been operational in these parts of Arnhem Land, and if so, had the only recently banned practice (outlawed in 1971) meant that the animals were still wary of humanity? Or was the co-existence more to do with a long, traditional understanding of each other’s’ needs?

I wondered whether the crocodile shooting/skin trade had ever been operational in these parts of Arnhem Land, and if so, had the only recently banned practice (outlawed in 1971) meant that the animals were still wary of humanity? Or was the co-existence more to do with a long, traditional understanding of each other’s’ needs?

We made the trip without mishap, arriving to find the community deserted, presumably out hunting. Tommy fired his shotgun into the air and Peter Jalara turned up about 30 minutes later, four magpie geese hanging from his belt. We completed his postal ballot form and he said he would have the others (Fred Mawanburrnga, his wife Mabel Langarangara, Joe Mangguludja) come across to Kupunga, later.

We had the help of an outward tide, and the sail for our return journey. There were a couple of cooked magpie geese ready for snacking upon our arrival, and a group of older men settled down with me in the shade of the school house.

I posed “Why did you decide to stay out here after that big bungal (ceremony) finished, right through the last wet?” Barney Geridawanga said “Too much trouble in Maningrida. Too much humbug, sickness, fighting. And the kids were getting away from us!”

I was talking with Frank the next day, and he repeated the same responses as Barney. “Me happy here; too much of ebrything. I got im house, tucker, water; dis is my country and my kid’s country. If I go away and leave im unprotected, someone, maybe Balanda, might steal im! We need plenty of soldiers in this country to keep im!”

“What about the kids?” Frank, with head slightly on the side said “We gottem school house, we gottem David (Mirawanga). He gottem all dem kids, from other side too, in dem morning and teach em good. Afternoon, they all finish up. It is more better for the kids to grow up here an know dare country. No humbug at Kupunga, like at Maningrida. The kids are better here in their own country!”

An emphatic endorsement of the benefits of returning to “proper” country, to reestablish modified, but nonetheless quasi-traditional authority. Frank talked about one of the young blokes – now in his late teens – who was now living back at Kupunga. His Mum had insisted he come out to country after a string of trouble at Maningrida, that had eventually seen him sent to a juvenile detention centre in Darwin.

After close to a year, he has settled down and is taking on quite mature responsibilities around the community. Maturation and possibly the traditional disciplines necessary for life in the bush!

Late in the afternoon, hunters have returned home, bounty distributed, as necessary and I note family groupings are settling around individual hearths! I see that Frank is stripping lengths of stringybark and his wife, Nancy is pulping and teasing the bark down into pliable fibres. She is using her thighs as a base to rub the fibres together, joining the individual pieces into lengths of string that she tells me will be woven into a dilli bag. It will be sold to the arts and crafts shop, at Maningrida.

Nancy’s older girls are working a stone mortice and pestle, grinding ochre that will be used to colour the string! Meanwhile, I note that Nancy also maintains an eye on a group of younger kids, playing in the shallows at the river’s edge.

Frank has drifted off and joined David and a group of young men, each with 12-gauge shotguns and heading into the swamp. Mmm that means goose for dinner!

Tommy is tinkering with the mast and sail he has adapted for the lippa lippa, while nearby, his wife and kids laze in the shade, occasionally calling out to other women. There is quiet laughter, and banter on the air.

Geridawanga and his wife seem to be asleep and I see their youngest children down at the water’s edge, playing with a new inflatable toy, purchased from the recent mobile shop. A voice, his wife’s, issues a cautionary note that has the kids briefly pause their games.

At dusk the hunters return. They have several geese between them and I noticed every family was soon plucking, singeing, and settling into the evening. I am invited to join the single men’s campfire.

The mosquitoes last night were terrible, although I was the only one who mentioned them! My swag was just a canvas square and a blanket – a mosi-net was still considered unnecessary, but that was to change, after this trip!

I borrowed a throw-net and collected three nice-sized mullet the next morning. Barney and I shared the bait and we sat by the river yarning for the next couple of hours. I got a couple of decent bites, while Barney had a barra on the line, subsequently lost in the landing!

Franked joined us at the water’s edge. We continued to yarn, while he busied himself making a new ‘butterfly-wing’ net. Instead of bush string, he was unravelling a length of old blue, nylon rope that had drifted up the river! He had made a light frame; I think from dried hibiscus wood. 3 lengths bound into a triangle and then covered with the woven nylon net. He repeated the triangle and weave, and bound the two sections together at the apex of the two longest ends. (Imagine a pippi, opened but still joined by the muscle, or a pair of castanets!)

Frank’s eldest son took me to a brackish pool the next day to demonstrate the net’s use. We waded into the warm, shallow water and holding the wings midway along the top frame, he proceeded to work the net, opening the two sides to form a barrier and then quickly bringing the two sides together around unsuspecting – Durnbal durnbal – foot long crustations – big marron-like prawns. In a matter of 30 minutes he had four in a dilli-bag suspended around his neck.

Frank and I continued to talk about country and his ideas for possible road access. He again talked about a dry season track that, while presently under a foot of water, was drivable from the middle of the dry season, through until after the first rains. He suggested we look at it later in the day, when the sun had lost some of its heat.

That afternoon I walked off across the mud flats behind the community. On a small rise on the other side, I found David Mirawanga sitting in the shade, stripping the bark off three lengths of mangrove wood. He says they will make a frame for his mosquito net! (Ah ha, so I wasn’t the only one getting bitten, just the one itching and scratching!)

With the frame done, he suggested a walk. We returned to the waterhole visited yesterday. He explained that while the Durnbal were here now, other seasonal bounty included the freshwater catfish – Bulia Mulali, the long-necked tortoise – Barnda, and a moonfish – Djingol. For now, there are huge numbers of leeches, each intent on extracting our blood.

A few hundred yards away, at the back of the sand dune fronting the nearby Arafura Sea, we came to three wells, one used exclusively for clothes washing, the other two reserved for drinking. All were adjacent to a small grove of bush apple trees – syzygium sp, and I think David advised that the trees were always an indicator of nearby freshwater.

We wandered off and my education continued as he spotted a delicate, thin, string-like vine growing in an area back away from the dunes. Mundbanda – yams he instructed, as I tried to focus and identify what he was pointing at. His educationally-honed patience came to the fore as he pointed out the small, heart-shaped leaf atop the vine. He traced the vine back from the leaf, to the ground and dug about 8”, and retrieved a small tuber. In the space of a few minutes David uncovered four. I seem to remember that he broke pieces of the tuber off the vine carefully and replanted the vine, still attached to a remnant tuber section.

Nearby was a tree laden with dark edible berries. They were about ½” in diameter and I had seen kids in the trees harvesting these before. I note that the greenants also liked the tree and their activities ensured the harvesters would come away covered in them. Not a huge issue, as their green abdomen, when eaten provides quite a refreshing citrus hit!

We approached the community from the direction of Lalarl-a-jiripa. David was talking about this area as a special place – in olden times – for dancing and ceremony. We continued walking, and as we came over a rise we casually stepped over a badly disintegrated lorikun, or log-coffin. A skull protruded from one end and David, equally casually told me that this was “… his daddy, properly, back in country.”

Late that afternoon I sat down with Barney, and two of his countrymen from across the river, Fred Mawanburrnga and Joe Mangguluda. Someone had accessed a damper, which we intermittently chewed, in between smoking cigarettes and discussions relating to old time Marian law. There was talk of the large ceremonial gathering eighteen months earlier, that had underpinned the decision to relocate permanently on country, away from Maningrida.

As a visitor, and a novice, I was keenly aware that the old men were delighted to participate in my introduction to ‘country’. There were boundaries, secret/sacred stuff that would never be broached, but that left a wealth of material up for discussion. David had sat down and at some point, brought out a written list of place names and activities. My lessons, mis-pronunciations and foot faulting achieved deep, gravelly guffaws from the guys. I found David’s notes carefully stored with my diary. His drawings are incredibly accurate – the eel-tailed catfish, at top and the fifth drawing, the large marron – Jarnbul Jarnbul.

Fred and Joe hopped into the lippa lippa, and went back to Manakodok-a-jiripa, as I retired back to my schoolhouse base for the evening.

At Dusk, David appeared with a haul of small whistle duck – Blanamirika, maybe twenty-five or so and left two with me. I had plucked, singed, and commenced to cook them by the time he returned from distributing the birds.

At Dusk, David appeared with a haul of small whistle duck – Blanamirika, maybe twenty-five or so and left two with me. I had plucked, singed, and commenced to cook them by the time he returned from distributing the birds.

The generosity from the whole community was humbling. Food was being shared, educational lessons for living with this rich country were being offered, and I was the recipient of unstinting, warm hospitality. I hoped I would be able to meet future reciprocity!

That evening David and I talked well into the night. He asked me about my job and why I had come out to Kupunga. Mmm the role of a Petrel Obbicer?

I talked about the new Prime Minister down south. The government wanting to help people living in the bush to achieve their own independence, using their skills and knowledge to shape the future they wanted for themselves, their kids and grandkids. I inserted myself as working half way between where the money and help was going to come from – Darwin and Canberra, on one side and communities, on the other, pursuing “self-determination”!

From what I was experiencing here at Kupunga, my generous interpretation of the government’s offer of independence, the opportunity to determine their own futures smacked of impertinent nonsense, ignorant arrogance, I thought, as I reread my words later!

David talked about the trouble he was having implementing his ideas for Kupunga, up against the day to day lore and practices being exerted by the older generation. While he talked passionately about kid’s schooling and getting vegetable gardens growing, my mind’s eye was seeing people reveling in an enjoyment of the security and wealth of their own traditional estates. There were obviously going to be some competing priorities, a sustainable balance between traditions and the enjoyment of western opportunistic insertions, like mobile shops, shotgun cartridges, flour, tobacco, tea-leaf! But the decisions, the choices had already been unequivocally made by this mob!

Access to Social Security benefits was providing cash flow to enable a few commercial inputs to community life. Generally, the inputs were temporarily replacing traditional staples, flour, sugar, guns, and traditional nutrition was probably more than compensating for the processed inputs.

There was another cash flow being generated by the arts and crafts. Weaving was producing bush string bags, pandanus fronds were being stripped, dyed and woven into beautiful mats and baskets, stringybark was providing canvases for artistic expression.

An adjunct to the mobile shops were the collection and documentation of this artistic output. Dan Gillespie was now coordinating the operation of Maningrida Arts and Crafts and at the conclusion of the shopping, people would present items. I cannot remember exactly but I think Dan was taking items on consignment, returning net returns to the artists on subsequent trips?

David was over early the following day. He had a pair of firesticks – ngurtka, and suggested I learn how to make a fire! He demonstrated, seated on the sand with the slightly flattish one of the two sticks, pinned, but protruding beneath his bent right leg. He had a small pile of teased-out bark placed below a burnt hollow on this stick. He dropped a pinch of sand into the hollow and proceeded to drill into it. Ten seconds, and it was smoking, thirty seconds, and the flames caught the bark!

“OK Balang, you have a go!” Under minute scrutiny, I drilled for all I was worth. The minutes passed, smoke arose but I just couldn’t maintain my speed or focus sufficient to get a flame to jump into the tinder! I did raise a couple of blisters!

And I did learn that both sticks were dried lengths of hibiscus wood, and I subsequently bought a set from the Arts and Crafts outlet. I secretly practiced and raised red welts, sometimes smoke but never any flame!

Mirawanga gave up and suggested we go for a walk. Over the morning we visited coastal, hand-dug wells. He mentioned that anthropologist Betty Meehan and archeologist Rhys Jones, both who spent considerable time with the Kupunga mob, had been to this series of wells.

One he named as Bunbuar, quite distant from home but apparently it never dried up. There was a Tamarind tree growing not far away and he said those olden times mob “…prom ober seas…” planted it. I had seen another similar tree, at Tjuta Point, I think there was another one on Entrance Island, all planted by the Macassan seafarers who were visiting, up until Federation, during the wet seasons, to collect the trepang, or beche de mer.

He was continually stopping to show me bush tucker. He talked about a different, cheeky, or non-edible yam that looked very similar to the one he cropped the other day. We never found it.

We headed away from the coast to two other water soaks. They were within the paperbark forests and to my untrained eye, looked like buffalo wallows. He named them as Malmal-a-jiripa.

We continued south as the melaleuca gave way to stringybark. We were crossing swampy country – Balpinarda – and eventually struck the dry season track – Angirrajunabir – connecting Kupunga and Maningrida. It was very sloppy, in places. We followed the track to the outstation.

There was more walking that afternoon. This time I was being hosted by Tony Monalia and Barney’s young nine-year old son, Stuart Yirawara. Tony bought a throw-net and we headed across to the dunes close to the river’s entry to the Arafura – Lalarl-a-jiripa – and onto the coast. We caught a dozen smallish prawns – Wakal – but, on the walk back across the tidal flats, Tony speared two large mud crabs – Malamiringa.

Over a latish midday meal of crabs and prawns, Tony confided that Frank Guramanamana had magical-powers that could make sick kids better. He said Johnny Bulun Bulun also had special powers and by holding a special stone in his right hand, he could fly! “Where does he fly too?” “All over the place!” They both draw that power from that Ginawinyun – that place on the coast with the tall tree that you see, near Nakalamandjara!

Barney wandered over later that afternoon. He wants to apply for an Aged Pension, mentioning that he was the same age as pensioners Charlie Anawudjara and Barney Ranidbala. He tells me he is worrying for that rupia, has trouble with his left eye and his eye glasses were recently broken by one of the children. I agreed to get an application form and to help him complete it on my next visit.

As the day cooled off, I joined the singlemen’s cohort, David, Stuart, Bruce Bali, and Tommy Steele and we went across to the edge of Balpinada to shoot whistle ducks. The swamp was covered in clouds of mosquitos but there were very few ducks. I am told the heavy harvesting yesterday has probably made the birds a little gun-shy, hence only about ten birds.

The birds were distributed and I appreciated the fact that Frank’s wife Nancy had my cooking fire alight and ready for the evening. I walked over and thanked her. Tony and David joined me for duck-stew and damper.

A final Petrel Obbicer duty was to update census records. I recorded:

Single men

David Mirawana (1947) parents dec’d

Tony Monalia (2/4/58) Jack ?& Margaret Jinjalara

Bruce Bali (30/4/60) Tony’s brother

Stuart Yirawara Barney and Nancy Djinbarr

Jacky Gumboa

Harry Mulumbuk Harry and his family were temporarily back at Maningrida

Frank Gurmanamana m Margaret Marrgawaitj 1st wife Nancy Bandiama 2nd wife

Betty (24/8/60)

Elua (17/4/63)

Ernie (17/4/65)

Mirabelle (13/6/68)

Florence (?) her parents are dead? and adopted

Barney Geridawanga m 1st wife (dec’d)

Nancy Djinbarr 2nd wife

Mary Djadbalak (Barney’s sister, sharing camp)

Marcia (14/6/68

Olivia (19/6/70)

Polly (11/8/72)

Cindy ) David Mirawana’s siblings

Rex ) living in Barney’s camp

Tommy Steele Gondara m Rhoda Bambula (1938)

Margaret Waiguma (Tommy’s aunty)

Georgina

Nancy

Jessina (Doris) (1/7/68)

Jacky Gumboa was an interesting older man. He carried a disability, wore a scrunched up old slouch hat and he was never without his several tobacco pipes. One was made from the movable section of a mud crab’s claw, the end was nipped off and the front held a plug of tobacco. I found they delivered an excruciatingly ‘hot’ smoke.

He had several other ones – I particularly remember a bush pipe, a hollowed length of wood, maybe 24” long with a tobacco plug holder at the other end. It was so long it always meant someone had to light it, while he dragged furiously from the other end.

He actively participated in most of the community activities, he smiled a lot, but I don’t remember him having a vocal input to any discussions. Several months later I saw Jacky, back at Maningrida, animatedly directing a huge mortuary ceremony.

The following day seemed to be a ‘lay’ day. People lazed in the shade of their camps. I generally followed suit, although I did feed a lot of bait to the crabs, in my efforts to land a fish. I caught up on some mosquito-denied sleep and as the day waned, I took myself off towards Balpinarda. The quiet was palpable, with a gentle on-shore breeze wafting through the melaleucas. I saw a couple of wallabies and quietly suggested they keep moving further into the bush!

The boys came over to my camp, suggesting we go fishing early tomorrow morning. They would borrow the boat and motor that Paddy Gunabandja and Andrew Mardadupa had brought back from Maningrida that afternoon.

We were on the river by first light, heading upstream. We passed a dozen crocs atop the banks, another reminder for me NOT to ever go swimming, despite community assurances! There where huge flocks of birds; ducks, geese, ibis already feeding in the shallows behind the river as we landed at Boula, a place where a small creek intersected with the Blyth River. From the top of the banks, we could see for several miles across the flats to where the trees demarcated the start of Balpinada.

We headed down stream and detoured, to remind the mob at Manakodok-a-jiripa that John Hunter was expected later that day. We pulled in briefly to Kupunga and picked up fishing gear, a damper, tea, billy and Andrew Mardadupa before continuing downstream.

We pulled in on the eastern back, near the mouth of the river – Muganera – where another group of Burada people had established themselves. The outstation was deserted, presumably everyone out hunting!

We turned the boat westward, along the coast for a couple of miles, eventually beaching at Ginajunya. We walked across to the sand dunes and in a shallow creek on the hinterland, David showed me where a stone fishtrap is installed. It had been built and is operated by Frank Gurmanamana.

Back at Lalar-a-jiripa, sightseeing over, we started to fish. We were all successful with several large catfish landed, David catching a 3’ shark. Tony had been using the throw-net and had a number of large mullet. Back at Kupunga a fish, damper and billy tea lunch preceded an afternoon nap. I later went with the young blokes’ duck shooting.

John Hunter still hasn’t arrived. This is only a concern for me, the rest of the community sensibly expects to see him when he arrives! I make a mental decision that if his boat hasn’t arrived by midday, I will ask David to guide me across to the Cadell River crossing, enabling me to walk from there to the Gardens at Gochan-jiny-jirra.

It is early and I am invited by the young men to join their clothes-washing expedition! We all hunker down around that 3rd well, the one designated for this chore and rinse, a little scrubbing and then throwing the clothes over convenient shrubs to dry.

An hour chatting on the beach and the washing is dry. It is agreed that David and young Stuart will guide me down to Ginawinun, where they will meet Andrew, who has the boat there fishing. The plan includes taking me in the boat further along the beach to Nakalamandjara, from where I can easily walk the twenty miles back to Maningrida.

I have my few clothes wrapped in my canvas swag, slung across my back and away we go. Margaret thoughtfully cooked a damper for my trip, and I have it stuffed inside my shirt.

I realise the close bonds that have been woven during my extended stay, a generosity offered without ceremony, a companionship, a nurturing care, and guidance extended to me as I bumbled around.

Later, reviewing my notes from the week, I grinned at my regular insertion of times – 10am we did this, 6.30pm off hunting – so far from the natural rhythms of the day, seasonal understandings, needs, opportunities. Oh well, I was given my first watch many, many years ago.

I think I had a couple of tears welling, as I followed David and Stuart westwards towards the coast.

It was still quite cool, virtually no wind but I could smell smoke. I looked behind me and saw/heard a “whosh” as Stuart applied a match to a clump of dried grass. Instant alarm at the prospect of incineration in this explosive grassfire. David also struck a match to a nearby clump. We paused, and I watched the fire quickly spread to several other adjacent clumps behind us. It died down, almost as fast as it flared, spurting as it reached another clump, died down, spurted.

With no wind the fire relied upon close contact, clump to clump. Yet again I felt I was in the presence of expert land management. I had seen the early dry season fires many times before – clearing out the dried, wet season sorghum, now bent and a tangle, loaded with lethally-sharp seed heads.

The fire crept along but within half an hour, the smoke, the flames had all but disappeared, leaving an extended family of Whistling kites high above, circling, swooping, crying out to each other as a freshly roasted morsel was devoured.

It took us about three hours to make the rendezvous with Andrew. He had a boatload of men and women that de-boated briefly to enable Andrew to run me along the beach the few miles to the western side of Anamaiera, or Shark Creek. (The western side saved me from swimming this unpleasantly-named, mile wide, tidal creek.)

John Hunter and Andy had just been boating past and came in to shore. Andrew departed to collect his passengers while John and I had a brief catch up.

It was twenty-three miles to Maningrida. The damper provided sustenance, and there were plenty of creeks to drink from, as I headed inland, off the coast. I arrived home a couple hours after sunset, tired, a few sore muscles but with a brain still buzzing as I continued to reflect upon that quite amazing week.